The Ecological Harm of Harm Reduction

Soaring harm reduction investments, rising drug activity, and an environmental crisis they're pretending not to see.

Harm Expansion

During the June 17 Clallam County Board of Health meeting, Health and Human Services Deputy Director Jennifer Oppelt praised the rapid expansion of the Harm Reduction Health Center (HRHC):

“We’ve almost seen a double of the amount of participants we’re seeing per month in harm reduction.”

According to Oppelt, HRHC’s monthly average jumped from 508 in 2024 to 974 in the first three quarters of 2025.

Yet Health Director Allison Berry insisted this surge did not reflect an increase in drug users:

“We don’t think there has been a change in the number of people who are using drugs during that time, but rather we are getting better access to people in the community who were not previously accessing services.”

But the county’s own reports contradict this narrative.

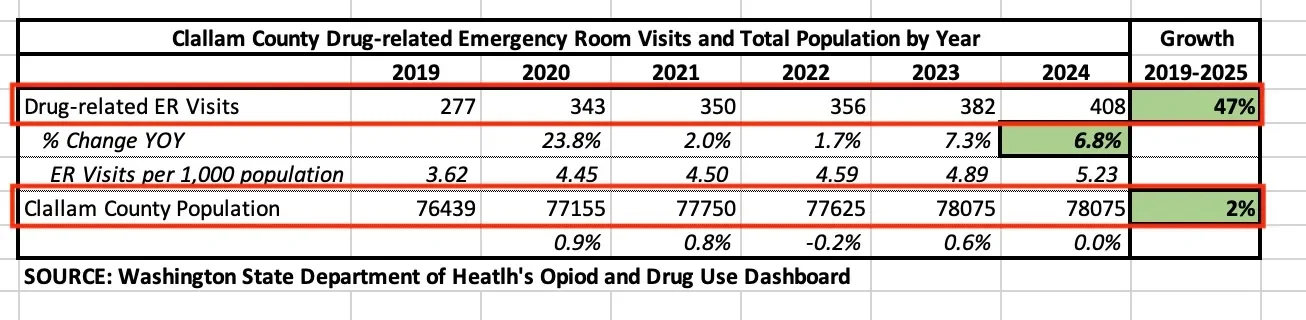

While HRHC encounters rose from 212 per month in 2023 to 508 in 2024, drug-related ER visits increased nearly 7% over the same period.

These indicators point to more drug use, not merely “better access.”

Survivors like Chelsea Jones have said plainly that drug-use supplies encourage new users — and some research supports this assertion.

Syringes, gloves, and tourniquets on the banks of Tumwater Creek.

A 2019 National Bureau of Economic Research study by Analisa Packham found that Syringe Exchange Programs (SEPs) were also associated with increases in drug-related arrests and drug-related emergency room visits — indicators of heightened street-level drug activity.

“These findings suggest that while SEPs are successful in reducing disease, lowering the cost of obtaining clean needles and other supplies unintentionally encourages more drug use, leading to more opioid-related overdoses.”

Unused syringes, pipe, sharps container, tourniquet.

A separate study from the Institute of Labor Economics by Doleac and Mukherjee found that expanded naloxone access was linked to more opioid-related emergency room visits, higher levels of fentanyl use, and increases in opioid-related theft, with no measurable reduction in opioid-related mortality. The authors attribute this pattern to moral hazard — when individuals take greater risks because the perceived danger is reduced.

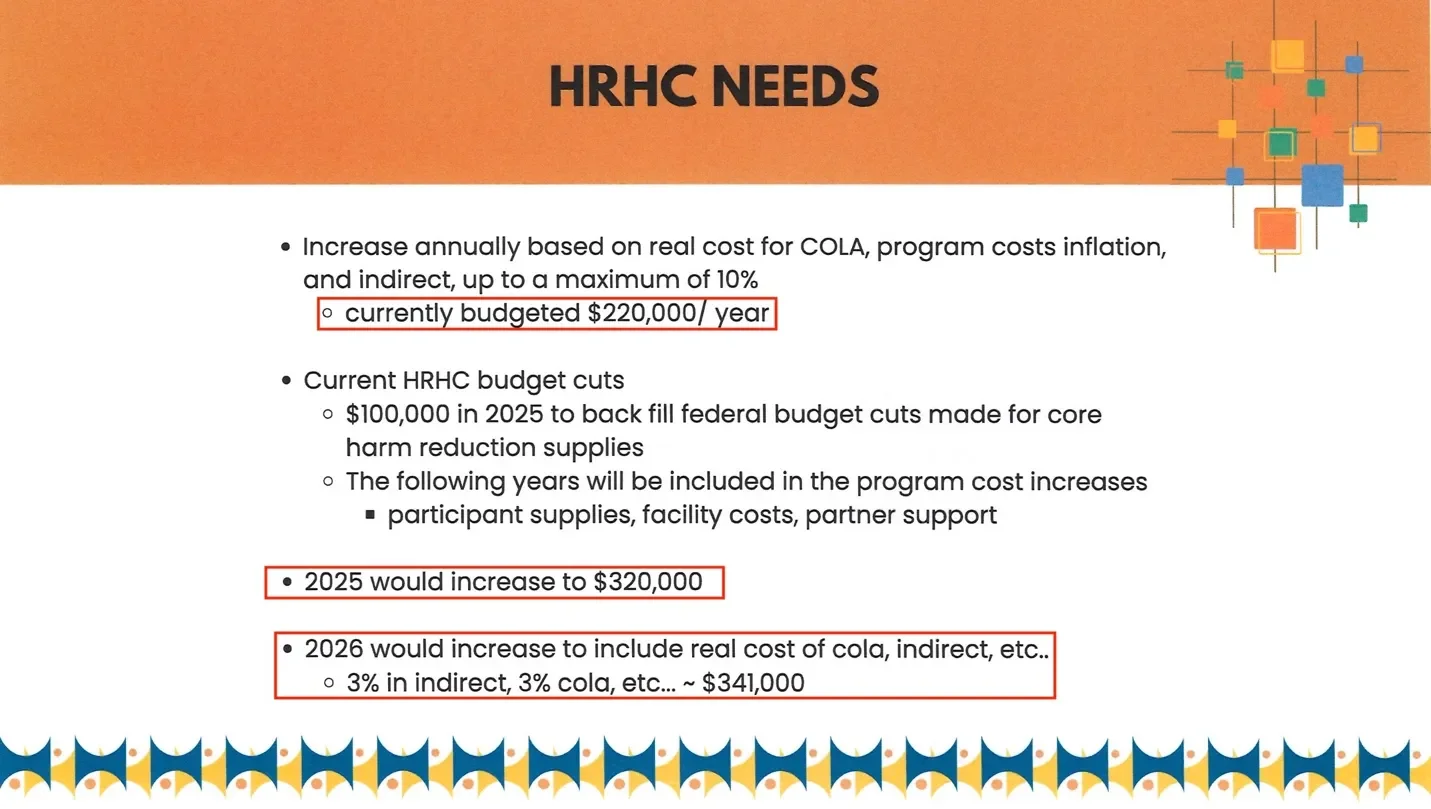

Dr. Berry offered no evidence to support her claim that an increase in drug users has not accompanied the 450% increase in HRHC encounters since 2023 — and the commissioners did not challenge it. Instead, they increased funding to HRHC from $320,000 in 2025 to $341,000 in 2026.

Growing a Local Disaster

As the HRHC has expanded in Clallam County, residents have observed a rise in open drug use and the trash that accompanies it.

A discarded glass pipe, tourniquet, and other supplies handed out by the HRHC now litter the banks of Tumwater Creek.

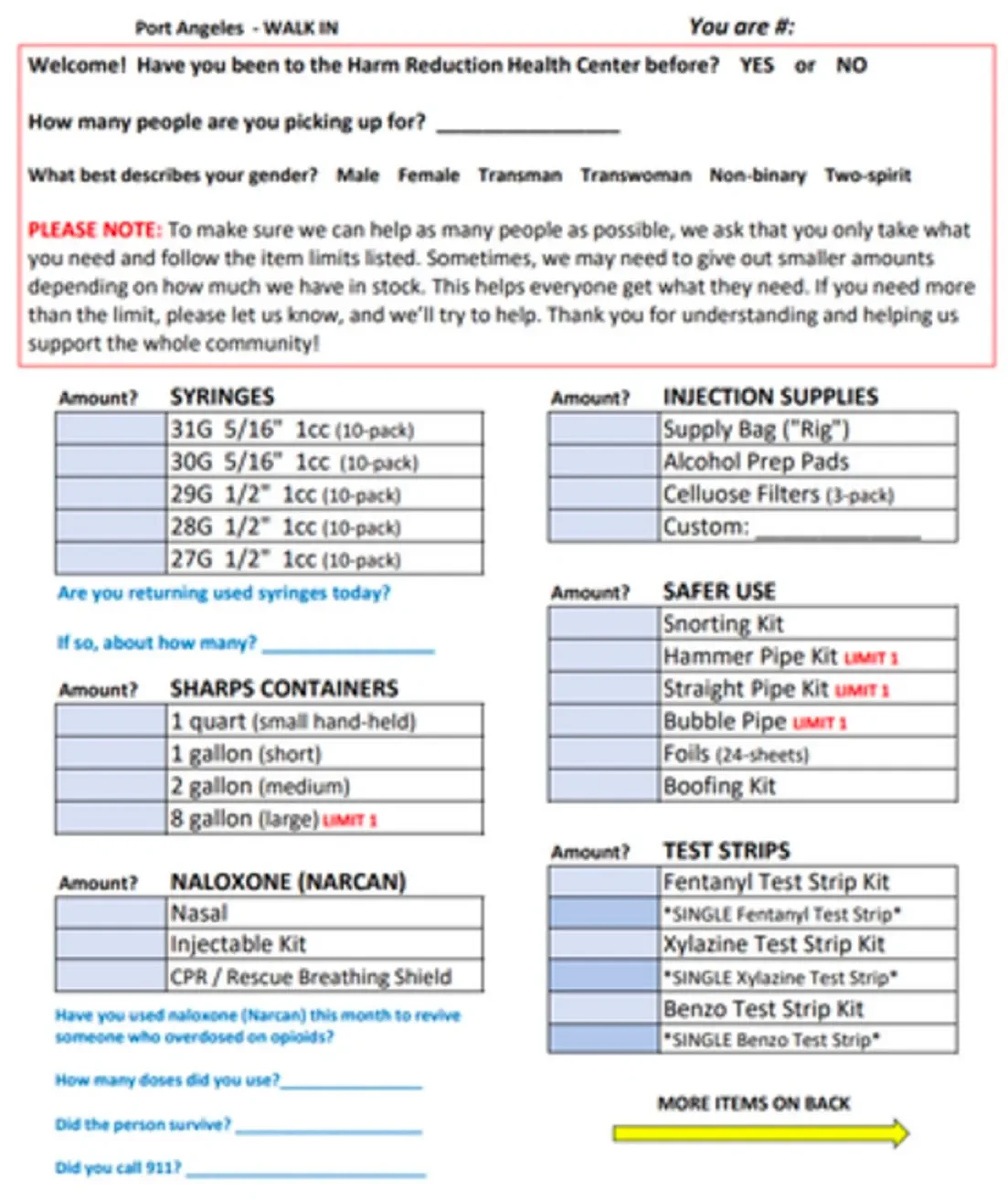

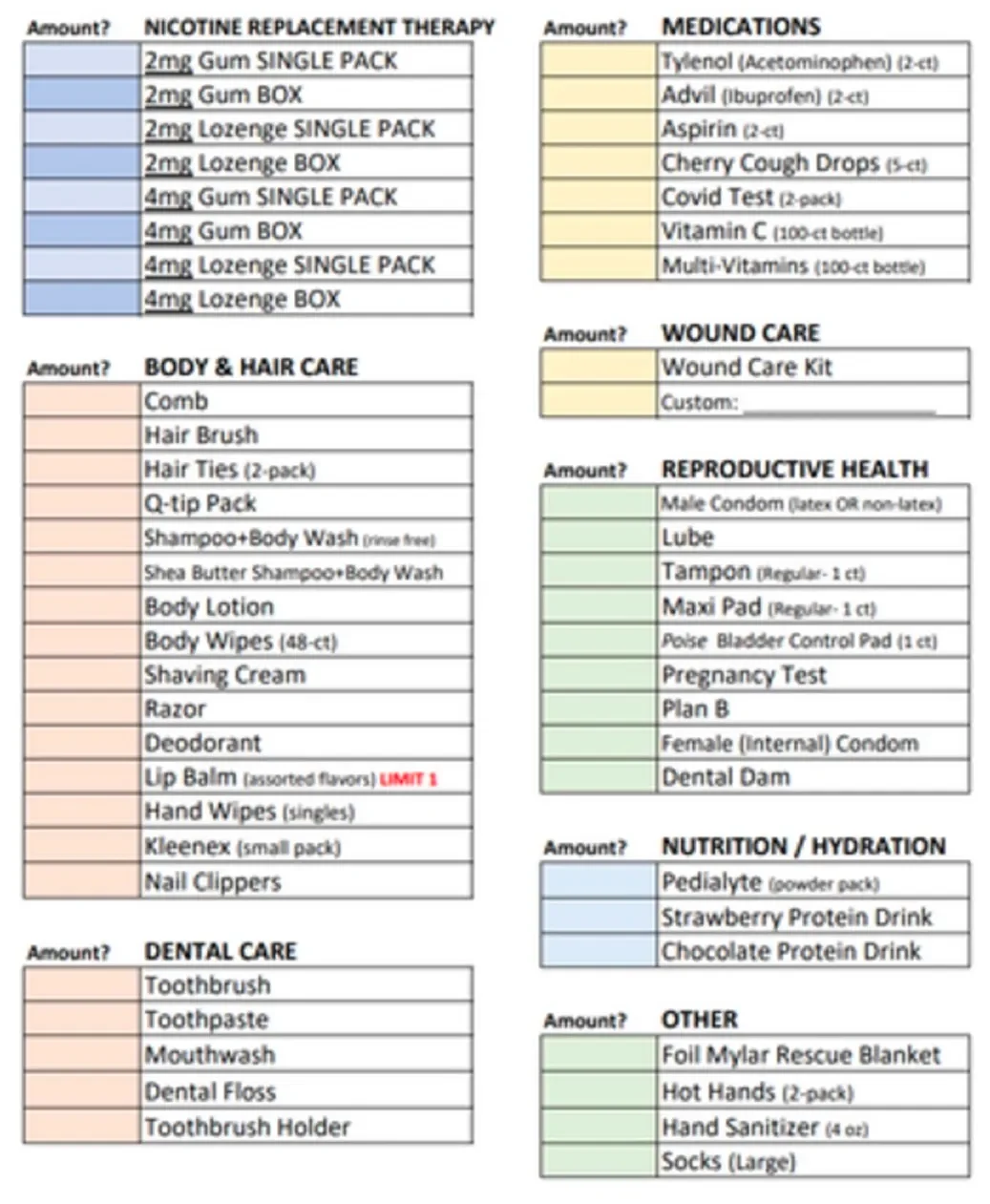

HRHC distributes an extensive menu of supplies.

On the list: syringes, snorting kits, pipes, foil, boofing kits, condoms, lube, hand warmers, space blankets — many of which are now scattered across forest floors, creeks, and waterfronts.

Harm-reduction waste has become a homegrown environmental crisis, with used and unused program supplies littering forest floors, waterfronts, and salmon-bearing creeks.

Tumwater Creek — just downstream of the recently completed fish passage project on Highway 101 — is littered with these menu items.

Foil, provided by the HRHC, can be used to smoke heroin, crystal meth, crack cocaine, and crushed fentanyl pills.

Public-Land Hypocrisy

During a recent presentation by Code Enforcement Manager Diane Harvey, Commissioner French stated:

“I really hope that we are using those tools that are available to us, that are legal, so that we gain the most leverage that we can to ensure people are not being destructive to their property or harming the productive use of an adjacent property.”

However, these same standards are not applied to public land.

The trash surrounding an illegal encampment is now being swept away by Tumwater Creek.

While county code enforcement intensifies on private property – with a recently added full-time code-enforcement officer in February 2025 and a part-time officer in August - hazardous encampments on public land remain largely unchecked.

An encampment grows beside Tumwater Creek with the pillars of the 8th Street Bridge in the background.

Unpermitted structures have been constructed along Tumwater Creek and on the bluff behind Country Aire in Port Angeles.

Structure on the bluff south of Country Aire.

Failure by city leaders and county commissioners to enforce their own ordinances is harming the productive use of property for Clallam residents and our tribal neighbors. In 2024, an unregulated tarp-and-tent village spread across Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe land along Tumwater Creek, just north of the 8th Street bridge.

When that encampment caught fire, a dark plume of smoke rose above the bridge — a visible warning of the crisis beneath.

Facebook post from summer 2024.

Today, the site is still littered with charred and melted debris—batteries, appliances, bicycles, needles, and discarded sharps containers, including items traceable to Clallam County Health and Human Services’ Harm Reduction Health Center. Together, they form a toxic mix poised to wash into Tumwater Creek with the next seasonal rise in water levels.

Meanwhile, additional unpermitted camps dot the banks upstream and downstream.

While county leaders aggressively regulate and prosecute private property owners for ordinance violations, they allow ongoing environmental damage on city and county land.

A car battery and tires await the rising waters of Tumwater Creek.

This contradicts Commissioner French’s own stated principle: that government must “safeguard the productive use of property.” In reality, leaders are neglecting enforcement on public land, undermining the productive use of adjacent private property, and exposing residents to increasing environmental and safety risks.

Tumwater Creek, which recently underwent a costly salmon restoration project, flows through trash-strewn encampments in Port Angeles.

This dereliction of duty threatens Tumwater Creek — immediately downstream of a major, recently-completed fish-passage restoration project on Highway 101.

Thank you, Clallamity Jen.

Citizens Clean Up While Government Funds the Mess

Volunteer groups, not county leaders, are doing the cleanup.

Harnessing nearly 1,000 annual volunteer hours, 4PA, a Port Angeles non-profit, has removed 350,000 pounds of trash and over 30,000 syringes from local habitats since 2021.

Recently, 4PA collected 1,000 needles in a matter of weeks, half of which were unused.

Meanwhile, the county continues funding the very programs that create these unpermitted landfills—while depending on a volunteer-run nonprofit to clean them up.

The CCD Blindspot

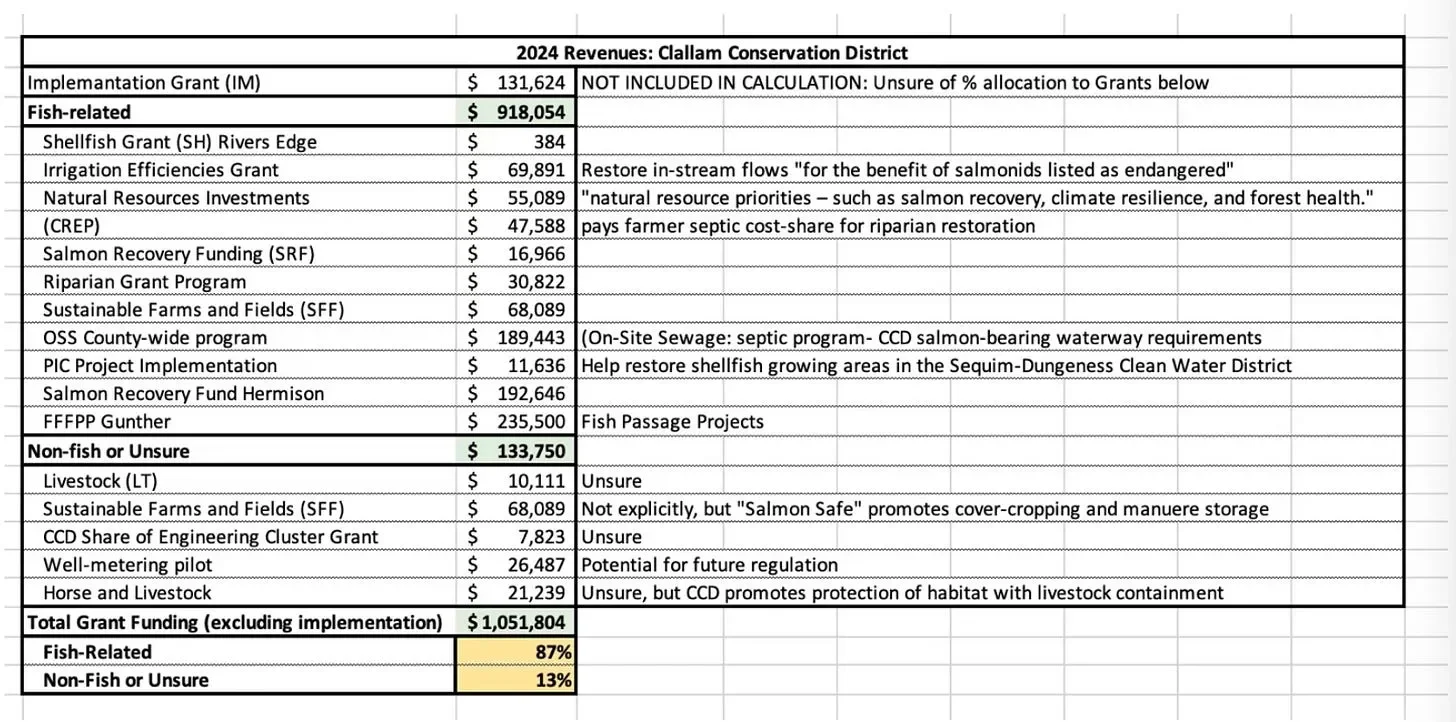

In late September, commissioners imposed a new $5 parcel fee without voter approval — a $2 million tax burden over ten years — to benefit the Clallam Conservation District (CCD).

CCD’s focus is overwhelmingly “fish-first.” At least 87% of its 2024 grant funding appears to be tied directly to fish habitat projects.

If commissioners expect citizens to provide an extra $200,000 a year to fund CCD, why don’t they also expect this salmon-focused organization to address the harm-reduction waste piling up along fish-bearing creekbeds?

Putting it all Together

Clallam County’s harm-reduction system is expanding rapidly, and harm-reduction waste now litters public lands, forests, and salmon streams. While commissioners resolutely enforce rules on private property, they overlook illegal encampments and hazardous debris fields on public land. Volunteers — not government — are left to clean up the mess, even as overburdened taxpayers are asked to pay more to fish-focused agencies that do nothing to address the environmental damage caused by harm-reduction programs.

This approach is failing residents, failing the environment, and failing the very people trapped in addiction. It’s time for accountability — and for leadership willing to protect both the community and the natural resources that make Clallam County a healthy and safe place to live.

“The greatest threat to our planet is the belief that someone else will save it.” — Robert Swan

What you can do

Write the commissioners: Let them know that harm reduction’s environmental harm must be addressed, not ignored — and that taxpayer dollars should not subsidize unregulated debris fields along our creeks, forests, and shorelines.

All three county commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov.